You’ve all seen at least one Egyptian statue and it had a broken nose. For people working in the museums, taking care of these ancient, precious vestiges, this might a very curious and strange question. Why do Egyptian statues have broken noses? For a man who is overseeing the The Brooklyn Museum’s Egyptian art galleries, this question is very simple to answer: the sculptures were inevitably damaged after thousands of years. Period. But still, why this pattern of defaced Egyptian statues?

“The consistency of the patterns where damage is found in sculpture suggests that it’s purposeful”, says curator Edward Bleiberg, from The Brooklyn Museum. The reasons are numerous: political, religious, personal or just vandalism. The challenge was to discern between the deliberate and accidental damage. If we think of a three-dimensional statue with a protruding nose, that is very easy to break, but what about those flat reliefs who also sport the smashed noses that we’re so used to?

The answer comes, though, from the ancient Egyptian’s belief that the soul and powers of a deity could live inside their physical image or that the essence of a human being actually inhabits its spitting image, the statue. So, defacing a statue could mean “deactivating an image’s strength”, finally states Bleiberg. Thus, the deity of person carved in stone could no longer have the same power and spirit after it had been defaced.

Without a nose, the statue-spirit cannot breather anymore, so basically, dies. Without ears, a the statue of a god cannot hear your prayers. In statues where human beings are offering to the gods, the left arm used to make the offering is cut off so the ritual cannot be performed anymore.

So here it is. Why most Egyptian statues have broken noses or broken arms and years. It’s not only time that has left its mark on them, it’s also the human hand who acting on some firm religious and spiritual believes.

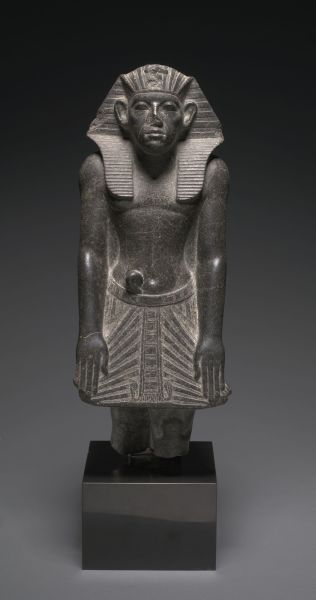

So, want to see some Egyptian statues without noses?

1.

2.

3.

4.

5.

6.

7.